Johnson’s Nightmare at Camp Seward — December 1861

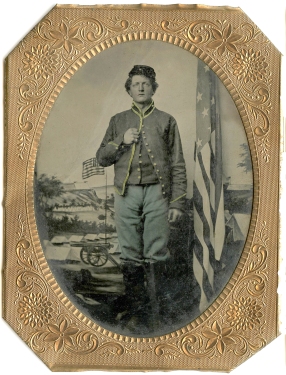

Adelbert Bailey

Residence: Williamsburg

Adelbert Bailey, born in Amherst, s/o Samuel B. Bailey & Violet Snow; m. 10/7/1869 Juliet Metcalf. Adelbert Bailey enlisted in the 31st Mass. Infantry as a sergeant 10/1/1861 and rose to full 1st Sergeant, serving until 9/9/1865. He was the last surviving Civil War veteran in Williamsburg, where the Baileys spent nearly all of their long married life together. Adelbert was listed as a tanner in his enlistment record, a currier in his marriage record, worked in the Haydenville Co. brass works in 1880, and finished his working life as the janitor in one of Williamsburg’s schools. His death record listed him as a retired machinist. Williamsburg Historical Society has several images of him. (Image used by permission of the Williamsburg Historical Society.)

In the third tier of bunks about half way down the hall were six as jolly good fellows as ever wore the blue, and we used to have our share of the fun, as well as the trials of Camp life.

One night we were having a good time after taps. The officers of the day came along and told us if we didn’t make less noise he would put us all in the guard house. Well we quieted down a little while and then Johnson said he would have the nightmare; we held him back awhile and then with nothing on but his shirt, he went over the side of the bunk with a yell that would have put a whole tribe of Indians to blush. Down the hall he went. The guard relief had just come in and they scattered as though the Destroyer was after them. Serg’t Canterbury finally caught him and the Col. threw a dipper of water on him, he thought it was time to come to; the Col. took him into his quarters and gave him a dose of something to strengthen him, and a half dozen willing hands lifted him up into the bunk; of course, the other occupants of the bunk were very anxious to know what was the matter. Serg’t Canterbury in relating the affair next day said the cords stuck out in Johnson’s neck as big as his wrist, and he never got hold of a man in his life so hard to handle.

It was a long time before we told the bottom facts of this little frolic.

En Route to Ship Island — February 1862

When the Reg’t left Boston there was a big demijohn of “Spirits Fermenti” forgotten by someone high in rank, but someone lower didn’t forget it. To bring it around in the jug was out of the question so hastily getting some bottles they soon had it in their knapsacks and with some lemons went on board.

The writer of this was awful seasick all the way out and one day one of the boys came to him and said he would give him something that would make him feel better, saying, that is good whiskey with lemons in it, take a good drink, he did so. A little while after a comrade who bunked with the first one came along and not knowing that his mate had been before him, said “Here you, just take a good dose of this and you will feel like a new man in a few minutes.” He did so without asking any questions, and starting in without stopping to taste it, down went a big dose, and up it come in a hurry. As soon as he could speak he asked what it was; being told that it was whiskey and lemon, he remarked that it tasted queer. The comrade who meant so well took the bottle and smelled it. “By thunder, that is our oil bottle.” By mistake he had taken the one that had sweet oil for keeping his gun from rusting. He rectified the mistake as soon as possible and the patient soon felt better.

Seabrook Inlet — March 1862

The Boys will recollect well how we lived after getting off Frying Pan Shoals, until we reached Seabrook Inlet, nothing but potato and salt for four days, potatoes one day and salt the next. We were hungry when we landed and about the first thing was to look for rations. How we went through the darkey quarters for hoe cake, officers and men alike, first come first served. Four of us borrowed revolvers from the officers and went after wild hogs up in the brush. We ran on to a little darkey girl about eight years old roasting oysters. We asked her to roast for us. We put about two bushel where they would do the most good and gave her a quarter, and started in for the hogs. The only one we found was at a deserted plantation which some darkies had killed and they were having a great time cooking it. They asked us to stop and help save it. They cooked and we ate and there wasn’t enough left to spoil when we got through. We reached Camp about daylight without any pork for the officers’ meals. We were to bring them some for the use of the revolvers. They were lucky to get those back.

There was a Reg’t there, I do not know the name, which brought us over coffee and boiled ham and hardtack and plenty of it. I sincerely hope if they were ever in the fix we were that some Mass. Reg’t had a chance to fill them as full as they did us.

While unloading the boat at this place to repair it the men would once in a while find something they could eat if they had a chance to get away with it. It was smuggling on a small scale, the officer of the guard was the Custom House. There was a barrel of peanuts, the Boys just tucked their pants into their boots and then filled them close to the waist bands with the nuts, and marched to their quarters all right. Little John Palmer found a barrel of ginger snaps and filled his haversack. When he passed the Custom House he was detained. He was taken up to the Colonel’s quarters and held for examination. The Col. was very particular to know just where the barrel stood, and told him to go to his quarters and not be caught in such a fix again. Johnny kept his ginger snaps, but the next morning the rest of the barrel was gone. Johnny said he would bet the darned officers got ’em because why was the Col. so particular to find out just where they were.

About December 1862.

Co. C had a splendid cook. One day, some of the boys lounging around his quarters said something about pie. He told them if they would get the stuff he would make them some, so they got a pass to go up the River to a store. Went nine miles. Got a can of cranberries, spices, &c. The cook made two pies out of the material and they cost a little over two dollars apiece, but they were worth it.

Port Hudson to Clinton — June 5, 1863

None of the Boys will ever forget the Clinton march. How hot it was. The morning we started from the running stream in the woods, (the only one I think we ever saw in Louisiana) we were told to take all of the water we could carry as we might not get any more till we got back there. We didn’t. At the orders to “Halt! Rest!” on the return the Boys didn’t hear it, but kept right on for water.

About the first thing after we arrived was a detail for picket. One of Co. C went down to the stream and brought up a cup full of water, as he came up the bank he was told to get ready for picket. He looked at the Orderly about three seconds and then he threw that cup down and jumped up and down on it till it bore no resemblance whatever to a cup. The Boys set up a shout and he felt better and went on picket. He never said a word, but it did him a power of good.

Organization as Cavalry — December 1863

The first lot of horses we drew did not supply all of the men. What few men in C Co. that got them were ordered to saddle up and go to New Orleans for more. Some of those horses were green, some of the men more so. Private [Marcus E.] Austin had a colt that had never seen service. Austin saddled him and mounted with all of the equipments. The horse stood like a statue. One of the boys asked him if his horse would stand the spur.

“Of course he will. If he won’t, he has got to,” and suiting the action to the word, he gave both spurs to his horse. The Boys will remember how we had those A tents set up on boxes. About ten feet from him was one with four boys sitting on the floor playing cards. The first thing they knew there was a game of pitch and Austin was trump. His horse didn’t stir his fore feet at all, but his hind ones. What a circle they described, and Austin had gone over his horse’s head with sabre, revolver and everything else he could take with him, and landed on top of the tent where the card players were. Of course that tent went down, and wasn’t there music in the air for a minute as they came crawling out from under that tent and Austin. It was some time after that before that horse had any spurs in him.

At Sabine Cross Roads — April 8, 1864

In Co. C were two men who enlisted in New Orleans. One was a German named Capline, one of the bravest, coolest men in the Reg’t. The other was an Irishman by the name of Hines — but was commonly called Teddy — just as cool and brave as could be, but often getting into a scrape,which he generally came out of with flying colors. At Sabine Cross Roads in close quarters with the enemy, one of the Johnies ordered Capline to surrender, at the same time calling him, giving him a title which was often used on both sides. Capline had just put a cartridge in his carbine. Without stopping to bring it to his shoulders, he said, “Me no son of a b — ” and pulled the trigger. Subsequent proceedings interested that Johny no more and Capline wasn’t a prisoner that time, but a short time after he was taken. At the time his haversack was pretty full and his guards got into a fight over it, and while it was going on he quietly walked back to his own side and picking up another gun was at it again. He didn’t lose over ten minutes.

Hines was taken prisoner at the same time. While the fight over the rations was going on he walked over where the Johnies had thrown down his carbine and sabre. He picked them up and started and got back all right. As he reached us I said to him, “What in the world did you stop for your arms for? Why didn’t you leave them and run?” He looked at me an instant and said, “Would I be a dom [sic] fool and have to pay for my little gun?” Knowing they were charged to him he thought he would have to pay for them sure if he lost them. A little while afterwards, I saw him walking to the rear with his carbine over his shoulder as though he was going home from his day’s work. I called to him, “Teddy, where are you going?” Without stopping he looked at me and said “Me animation [sic] is all gone.” He wasn’t the only one whose animation [sic] was gone. I told him to wait a minute and there would be plenty of animation. He stopped, sat down at the foot of a tree, took out his pipe and filled it and smoked as coolly as if he was in the barracks in New Orleans. As soon as the animation [sic] came, he filled his cartridge box and pockets, saying he guessed he would have enough this time to last awhile, and the way he proceeded to issue that animation [sic] to the other side was a caution.

Pingback: 1862: Constant E. Southworth to Frank Southworth | Spared & Shared 22